Spearheaded by burgeoning scientific and clinical research literature, psychedelics have reached a level of media coverage and popular interest that has not been seen for over half a century. By “psychedelics,” we are referring to the unique class of substances that includes psilocybin (the active compound found in so-called “magic mushrooms”), LSD, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), ayahuasca, 5-MeO-DMT, and mescaline – each of which occurs in the natural world (except for LSD, which is a semi-synthetic compound).

Do Chiropractors Diagnose & Treat Disease? How the Controversy Began

In 1906, D.D. Palmer was convicted of the unlicensed practice of medicine. The basis for his conviction was that he had violated Iowa state law by publicly proclaiming to cure or heal. Palmer also failed to obtain a certificate from the state board of medical examiners and register with the Scott County Recorder.1

It may come as some surprise, but in the early years of the profession, the founder and his son, B.J., did profess to cure and heal a wide variety of human ailments (Figure 1). However, D.D. Palmer's claims to cure or heal patients of named disease processes with chiropractic adjustments is well-known to students of chiropractic history. After all, chiropractic sprang from the roots of D.D.'s magnetic healing practice, where Palmer believed he was divinely endowed with a "special gift" that allowed him to cure disease with his hands.2

Unfortunately, D.D. Palmer's beliefs regarding his personal healing powers and that of his newly founded healing art, cast in print, collided with Iowa state law, resulting in his conviction and incarceration in the Scott County jail. He lamented this fact in a letter written from his jail cell to Dr. Solon M. Langworthy:3

"This is the first letter written from my new office which is furnished by the county. I have given two adjustments which gave relief – must not say 'cure or heal' for the State Board has a copyright on that."

A Competitor Arrives on the Scene: Solon M. Langworthy

Solon M. Langworthy was among D.D. Palmer's earliest graduates. In addition to his chiropractic degree, Langworthy also studied osteopathy in Kansas City and had a degree in business from Bayless College. After his graduation from the Palmer School in 1901, Langworthy, a Dubuque, Iowa native, located in Cedar Rapids, Iowa to establish his chiropractic practice and later a school incorporated as the American School of Chiropractic and Nature Cure.4

Langworthy became one of the Palmer's greatest competitors and challenged the Palmers for leadership of the profession. While in Cedar Rapids, he became a respected member of the community and built a thriving practice and chiropractic equipment manufacturing company. Langworthy and his wife, Ora Mae, were active in their church, often lending their musical talents as organists. And Langworthy was often the vocal soloist for many of the church's services.4 Recently, I learned he was also an active member of the Cedar Rapids Country Club, rubbing shoulders with the city's elite.

Langworthy Exploits a Loophole

As D.D. discovered, professing to "heal or cure" human disease was legally defined as the practice of medicine in Iowa at that time. Technically, one could claim they were not in violation of state law if they simply avoided that assertion.

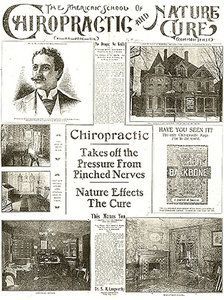

Figure 2 is a full-page advertisement from a Cedar Rapids newspaper for Langworthy's American School of Chiropractic and Nature Cure from January 1904. As you can see, Langworthy appears to exploit the technicality in Iowa law by not claiming the chiropractor "heals or cures." Rather, his marketing maintains that chiropractic adjustment takes pressure off pinched nerves and then nature's healing power cures the patient.

Whether D.D. Palmer made this loophole in the law known to Langworthy or Langworthy figured it out for himself, one thing is known for sure: No evidence exists that indicates Langworthy was ever arrested, indicted or tried for the unlicensed practice of medicine. I have searched the files of the Cedar Rapids newspapers over the time Langworthy was in practice there and also hired a private investigator to search legal documents to confirm this fact. Conversely, B.J. Palmer was indicted in Scott County for practicing medicine without a license in April 1903.5

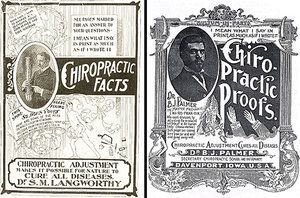

Figure 3 is a side-by-side comparison of a Langworthy advertising booklet and one produced by B.J. Palmer. These booklets are from the same year, 1903. Note the subtle differences in the claims made on the covers of these publications. Langworthy exploits the loophole in Iowa law, while B.J.'s advertising copy clearly violates the letter of the law.

I first proposed the hypothesis that Langworthy avoided prosecution by exploiting this legal loophole in a lively discussion on the Association for the History of Chiropractic's Facebook page sometime around 2015. Recently, chiropractic historian Dr. Timothy J. Faulkner echoed my proposal:5

"Soon Langworthy also made the subtle, but significant change in his advertisements. By 1903, Chiropractic Facts newspaper advertising was produced by Langworthy, with the statement that, 'Chiropractic Adjustment Makes it Possible for Nature to Cure All Diseases.'

That Langworthy made a change in his publications and the Palmers did not continue with the 'nature curing' wording would seem to indicate that Langworthy may have understood the subtlety of word usage in the profession's advertisements necessary to avoid legal prosecution in Iowa. Whether this made a legal difference in the prosecution of the Palmers compared to Langworthy not being prosecuted is unknown.

To the modern chiropractor, the statement that adjustments free the nerves so nature can do the healing is a common idea. It is more accurate than the early Palmer ads saying 'chiropractic' or the 'adjustment' is what cures. Solon Langworthy may have been simply stating this more refined chiropractic philosophical idea in his ads."

How These Historical Events Have Shaped the Present Controversy

Do chiropractors diagnose and treat disease? I have seen that argument play out in professional meetings and on social media more times than I can count. The evidence presented here indicates that in the early years of the profession, D.D. Palmer and his son, B.J., claimed to "heal and cure" human disease. That placed them squarely in the sights of politcolegal medicine, resulting in the conviction of the unlicensed practice of medicine by the senior Palmer. Slightly "tweaking" the language used may have been an early strategy to avoid legal entanglements and may have been used successfully by Solon Langworthy to retain his liberty.

These early events have shaped how chiropractic has been codified into law in the United States and around the world. In some localities, what I have called "The Langworthy Doctrine"6 prevails and chiropractors are subluxation detectors and correctors. In other localities, such as Illinois, where I practice, chiropractic is defined in a much more broad sense. Illinois law defines the practice of chiropractic as " [T]he treatment of human ailments without the use of drugs or surgery."

Regardless, the present circumstance of the legal status of chiropractic in any locality has its origin in these historical events.

Editor's Note: The Association for the History of Chiropractic (AHC) has preserved the credible history of the profession as its sole mission through the publication of the scholarly journal, Chiropractic History. Stories such as this one may be accessed through the pages of the AHC's journal (www.historyofchiropractic.org).

References

- Barker AP. "Judge Barker's Instruction to the Jury." The Chiropractor, 1906;April-May:32-37.

- Palmer DD. "I Don't Believe in Magnetism; It is a Humbug." The Magnetic Cure, 1896 Jan:1.

- Palmer DD. Letter to SM Langworthy in Cedar Rapids, IA. The Chiropractor, 1906 April-May:22-24.

- Troyanovich SJ, Gibbons RW. "Finding Langworthy: The Last Years of a Chiropractic Pioneer." Chiro History, 2003;23:9-17.

- Faulkner TJ. The Chiropractor's Protege: The Untold Story of Oakley G. Smith's Journey with D.D. Palmer in Chiropractic's Founding Years. Rock Island, IL: Association for the History of Chiropractic, 2017.

- Troyanovich S, Troyanovich J. Chiropractic and type O (organic) disorders: historical development and current thought. Chiro History, 2012;32(1):59-72.